The 2015–2016 teaching fellows, reflect on their year at the d.school, share a new set of d.school learning experiences, and embrace the ambiguity that lies beyond.

Out with the old and in with the new

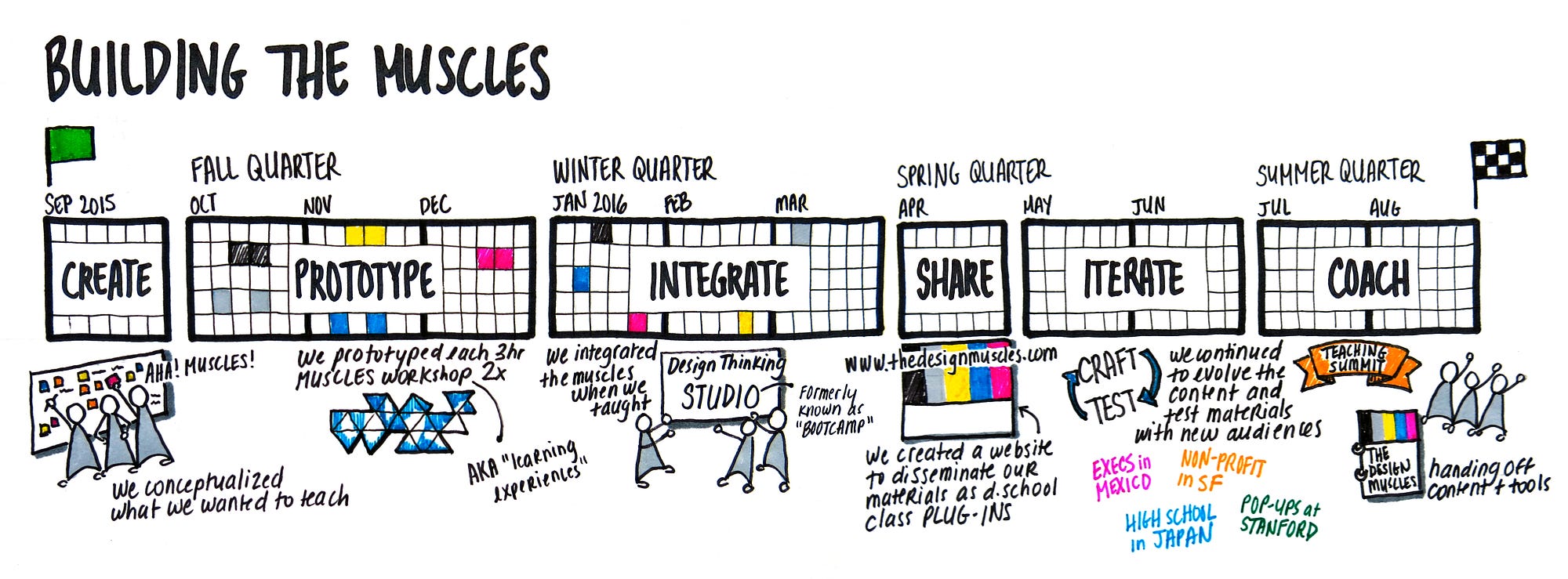

We’ve entered the last few days of our Teaching Fellowship at the Stanford d.school. We have a brief moment to collect our thoughts, archive our Google Drive, and reflect on the year that went whooshing past before we turn our positions over to the new Teaching Fellows. It’s strange to see our successors wandering the halls, a whole year of newness and excitement ahead of them.

We were an experiment for the d.school last year. They had never hired experienced design professionals as Teaching Fellows. Hannah Jones came with a PhD in design and 13 years experience in academia, running a Master’s program in Design Futures at Goldsmiths University of London, UK. Andrea Small arrived with 10 years as a practicing designer, most recently as Strategy Lead at Yves Behar’s fuseproject. Nihir Shah, the only Stanford Alumni, graduated the previous year from the Stanford Design Program after working in engineering, marketing and furniture design.

As professionals, we came in with strong points of view and fresh ideas about the culture and practice of design. Collectively, we sought to contribute something that might disrupt, critically challenge, and advance the status quo.

The ambiguous origins of the Design Muscles

For the three of us, the year began with a mega dose of ambiguity. The d.school embraces ambiguity to prompt creativity, but we were shocked when our objectives, timelines, goals, and the entire year ahead of us were so undefined. We started with an ambitious challenge — to create and teach five new ‘learning experiences’ in just five weeks. These learning experiences could be any format, any length, any topic and for any number or type of participants. As designers know, a lack of constraints can be just as limiting as too many constraints. To work through the lack of constraints, we allowed ourselves to start from any place — aspirations, tools, formats, topics, or learning outcomes — and then engineered or reverse-engineered complete learning experiences from there.

One such starting point involved using physical arrows in the real world to point out ‘bad design’. The arrow was a prop that Hannah originally made for designers to point out awkward urban spaces in London. It was simple, fun, and provocative, and we loved how it put students in the real world. We built a workshop using the arrows to point out bad design hidden in plain sight on Stanford’s campus. After prototyping the experience a few times, we began to realize that the value was less about recognizing bad design and more about the power of noticing.

After prototyping our noticing workshop a few times, we decided to start thinking about the next learning experience, this time starting with a theme rather than a tool. We were drawn to ambiguity, as it mirrored our past design experience and current situation, diving headfirst into our undefined, new roles.

The metaphor takes shape

A realization was beginning to emerge. We had designed one learning experience around the value of noticing and another on ambiguity, and we felt a connection. Both were intuitive things designers deal with or practice all the time, but are generally not taught in a formal way. We asked ourselves, “What other intuitive skills do designers have that make them better designers? Skills that develop through practice or are inherent in the design process and collaboration?”

Picking the five wasn’t a scientific process. We brainstormed, voted, and landed on negotiation, metaphors and critique to round out the five. They evolved out of personal curiosities as well as conversations within the d.school community. In addition to ambiguity and noticing, we are passionate about the Silicon Valley’s culture of critique (or lack thereof) and its importance in collaboration; experimenting with the notion of design as negotiation; and exploring metaphors as tools for synthesis and ideation.

We started to refer to these five topics as ‘design muscles’, things that serve as design fundamentals and improve with practice. The metaphor of ‘muscles’, ‘exercising’, and ‘practicing’ felt right. In sports, coaches help athletes discover their talents and improve. In the same way, building and strengthening Design Muscles calls for careful coaching or facilitation.

We feel the d.school takes a very Nike-esque approach to design; just as Nike believes everyone is an athlete, the d.school believes everyone is inherently creative. This philosophy has been widely discussed. As Paola Antonelli said recently, “Putting lots of Post-it notes on the wall is not going to make you a designer.” Just as Nike sponsors professional athletes while still encouraging all people to be active, the d.school coaches creativity in designers and non-designers alike (and yes, there are a lot of Post-its). To us, the Muscles are skills that support anyone’s creativity and exist outside of specific projects and processes, in the white space of design.

Working outside ‘the process’

There is so much debate about ‘the process’. (Is there a process? What is the process? How is it taught and mastered?) We felt the d.school already offered a wide range of classes, tools and learning experiences that support and teach the process (empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and test). As a challenge to ourselves, we were excited to avoid the process conversation all together and see what happened.

Teaching the untaught aspects of design

Great designers are masters of negotiation, critique, metaphors, noticing and ambiguity — and a slew of other things — not just research, ideation and prototyping. However, we assume that (new and experienced) designers are actually good at these skills because they are such a huge part of design. Our learning experiences free up the constraints on people’s creative ability, not by teaching them steps, but by bringing their awareness to their shortcomings and giving them tools to improve and continually practice.

Why are they different?

They’re complementary. Some of the Muscles are not completely unique. Skills like using metaphors are taught in design education and negotiation techniques are practiced in business. These learning experiences are different because they were designed to be integrated into and complement existing design thinking curriculum.

They’re connected. After recognizing and exploring the theme of the Muscles, we decided to create five connected learning experiences. Past Teaching Fellows created disparate experiences, but we chose to stick with one theme and take it as far as we could. The Muscles are holistic. Each muscle does not flex in isolation but works as part of a (muscular) system.

They equip people, rather than delivering process. The Muscles hone and strengthen designers’ abilities for when they enter a design process or project. They strengthen a designer’s core, rather than handing them a recipe for design.

Going the distance

We were thrilled to receive a runner-up Core77 2016 Design Education Initiates Award. Our aspiration is to further develop the Design Muscles content and make it widely available to people outside Stanford. It would be exciting to see the Muscles integrated into or bridging different design specialisms. And we’d love to see how different cultures, communities and organizations might add to the list of Muscles, reflecting their various perspectives and contexts. We see potential for a new type of boot-camp that teaches all the Muscles and equips design thinkers with new strengths in creative problem solving, or a series of published guides available to all designers looking to up their game.

We haven’t had much time to stop and reflect upon our journey during this past year. Now that we’ve emerged on the other side, we’re proud of we’ve collectively accomplished. We wish there was more time to take it even further, but what designer doesn’t? We can’t wait to see what the new Fellows create. We hope that people continue to build and integrate the Muscles. With diverse perspectives, new muscles will emerge to build a stronger, more creative world.

Credits

Andrea Small, Hannah Jones, and Nihir Shah